Richard Buckminster Fuller was born in Milton, Massachusetts, on July 12, 1895. His parents were Richard Buckminster Fuller and Caroline Wolcott Andrews, and he was a great-grandson of Margaret Fuller, a famous American writer, critic, and women’s rights activist affiliated with the American transcendentalism organization.

Fuller grew up on Bear Island in Penobscot Bay, off the coast of Maine, and had his kindergarten in Froebelian. He was unsatisfied with how geometry was taught in class, arguing with the concepts that a chalked point on the chalkboard signified an “empty” mathematical point or that a line might extend to infinity. These seemed nonsensical to him, which led to his study on synergetics.

He frequently built stuff out of resources he discovered in the forests and made his own pieces of equipment. He explored creating novel equipment for small boat human powering. Then, by the age of 12, he had devised a ‘push pull’ mechanism for driving a rowboat using upturned umbrellas linked to the transom with a basic oarlock that enabled the operator to look ahead and guide the boat toward its target.

Buckminster Fuller studied in Milton Academy in Massachusetts before enrolling at Harvard College, where he was a member of Adams House. However, Fuller was never able to finish his official schooling. He was dismissed from Harvard two times: once for blowing all of his money on a vaudeville group and again, after being readmitted, for “irresponsible behaviour and disinterest.” According to his assessment, he was a non-conformance outcast in the fraternity atmosphere.

Fuller’s Works And History

In Canada, Fuller landed a job in a textile factory and subsequently became a worker in the meat-packing sector between semesters at Harvard. He also worked in the United States During World War I, where he served in the Navy as a marine radio operator, an editor of a newspaper, and the captain of the crash rescue boat USS Inca. Following his release, he returned to the meat packaging sector, where he gained managerial expertise. He married Anne Hewlett in 1917, and in the early 1920s, he and his father-in-law created the Stockade Building System for manufacturing lightweight, waterproof, and fireproof homes.

His Struggles

Buckminster Fuller remembered 1927 as a watershed moment in his existence as his daughter Alexandra died in 1922, just before her fourth birthday, following symptoms from polio and spinal meningitis. Barry Katz, a Stanford historian, discovered clues that Fuller was struggling from melancholy and anxiousness around this stage in life caused by Fuller’s rumination on his child’s death, assuming it was related to his wet and draughty living circumstances. This fueled Fuller’s interest in Stockade Building Systems, which promised to build inexpensive, energy-efficient houses.

Fuller was fired as chairman of Stockade in 1927, at the age of 32; at the same time, his wife gave birth to their daughter Allegra, compounding their financial difficulties. On lengthy treks about Chicago, Fuller drank heavily and pondered the answer to his family’s problems. Fuller even considered death by drowning in Lake Michigan in the late fall of 1927 so that his wife and children may gain from a life insurance claim.

His Resolution

However, he ended up changing his mind and promised to “search out the principles underlying the world and help progress mankind in conformity with them… discovering methods to achieve so much with so little so that all individuals worldwide might have more and more.” Hence, by 1928, Fuller resided in Greenwich Village and spent most of his leisure at the famous café Romany Marie’s. He had invested an evening conversing with Marie and Eugene O’Neill.

In return for meals, Fuller accepted a position beautifying the inside of the café, gave impromptu lessons numerous times per week, and displayed replicas of the Dymaxion at the café. Isamu Noguchi came in 1929, having been guided there by an old acquaintance of Marie named Constantin Brâncuși, which led to Noguchi and Fuller cooperating on various projects. This includes designing the Dymaxion automobile based on previous work by Aurel Persu that led to the start of a lifetime partnership.

Fuller spent half a century developing various concepts, plans, and innovations, notably in the areas of practical, low-cost accommodation and mobility. He meticulously chronicled his existence, beliefs, and thoughts in a daily notebook (later dubbed the Dymaxion Chronofile) with twenty-eight volumes. Furthermore, Fuller founded several of his projects with inherited monies, occasionally supplemented by cash spent by his partners, such as the Dymaxion automobile project.

His Achievements

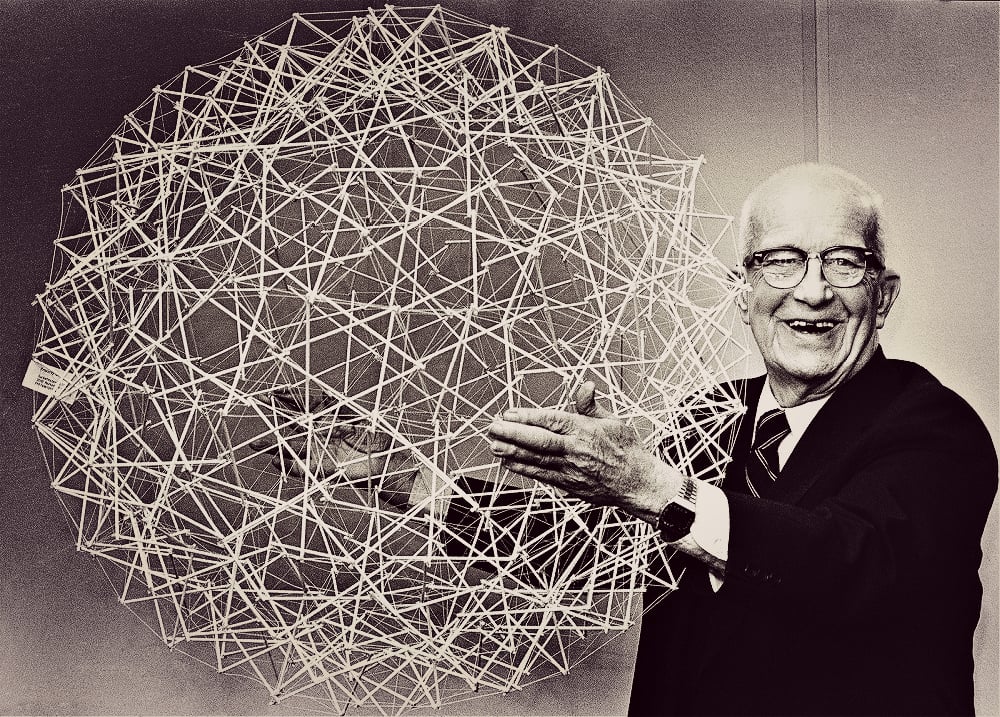

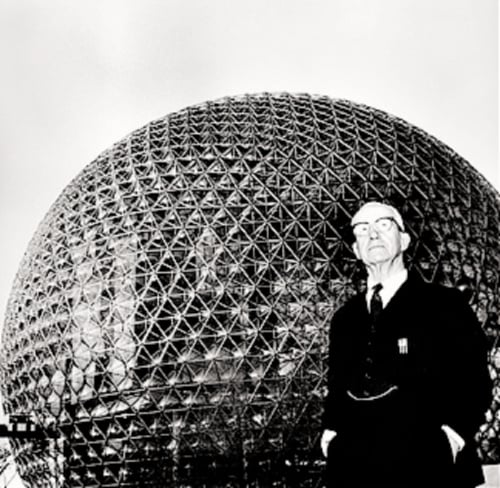

Global recognition emerged in the 1950s with the achievement of massive geodesic domes. In 1949, Fuller gave a speech at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, where he encountered James Fitzgibbon, who became a close friend and collaborator. Fitzgibbon was the chairman of Geodesics, Inc. and Synergetics, Inc., the first geodesic dome licensees. Fuller received computer estimates for the lengths of the domes’ borders from Richard Lewontin, a recent faculty member in genetic studies at North Carolina State University.

Moreover, Fuller predicted that human cultures would eventually depend mostly on sustainable sources such as solar and wind-generated power. He envisioned a day of “Omni-successful learning and nourishment for all mankind.” Fuller referred to himself as “the ownership of the cosmos,” In a subsequent radio broadcast, he proclaimed himself and his works to be “the possession of all mankind.” The American Humanist Organization recognized him as Humanist of the Year in 1969 for his decades of effort.

Fuller’s Legacy and Death

While R. Buckminster Fuller’s name may not be familiar, his ideas have left an everlasting mark on the globe, most notably through his famous Geodesic Domes. Indeed, according to The Boston Globe, over 200,000 Domes have been built across the world since their beginnings. Conversely, his concept of the Geoscope and World Game sounded fantastical and idealistic to many but has proven to be nothing less prophetic in our post-modern society of computers and telecommunications. According to Britain’s most renowned living architect, Norman Foster, his Dymaxion designs have had “an enormous influence” on the realms of science and innovation.

R. Buckminster Fuller, widely known as the inventor of the geodesic dome, died from a heart attack Friday at the Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles while seeing his gravely ill wife. He resided in Pacific Palisades, California, and was 87 years old when he died. However, his remarkable innovations and vast knowledge, which he shared with many, will live on in everyone’s memory.